In France, the Yellow Vests have left the roundabouts, but in Réunion, a convergence called “QG Zazalé” still stands. Located in Le Tampon, in the south of the island, it is composed of a community of activists committed to building their project of social justice and making their citizen voice heard.

Surrounded by the constant flow of cars, amidst plantations and animals, they debate ecology, the decolonial question, and act for food sovereignty and autonomy.

Gradually, this experimentation of a new, subversive, and political world is gaining momentum and questioning social issues and access to land.

Some Réunionese are questioning the island’s strong dependence on mainland France. They advocate for local and tailored solutions to address issues such as poverty, unemployment, etc., and to regain the dignity of the people.

They denounce the application of measures copied from the Western model to manage local issues. For example, in the economic, agricultural, territorial planning, and social fields.

The roundabout serves as a laboratory for political, ecological, and social experimentation to conquer Réunion’s sovereignty.

The history of Réunion partly explains this situation. Indeed, during the colonization of the island, the land was allocated to settlers from France. It was the slaves and then the contracted workers who exploited and developed them.

The end of slavery did not lead to a redistribution of land. On the contrary, heavily compensated, the large landowners were able to expand their estates at the expense of the poorest and the newly freed.

In 1946, the end of decolonization and departmentalization reinforced the grip of large landowners and favored the creation of new monopolies.

The composition of the Réunionese population reflects a history of mixing. The first inhabitants of the island were Franco-Malagasy (French settlers and Malagasy slaves), who mixed with descendants of slaves and indentured workers from the Indian Ocean region, mainly from East Africa.

During the slavery era, colonization, and until 1981, 35 years after Réunion’s departmentalization, maloya music was banned from radio and television broadcasts. This music and its associated dance evoke the African roots of the slaves and part of the Réunionese people. In the 1970s, the Ziskakan collective rose to restore the Creole language and various forms of artistic expression to their right to exist in the public space.

Today, the combined effects of cultural homogenization through globalization and the internalization of a sense of inferiority of the Creole language and culture fostered by assimilationist policies, create an urgency for transmission to younger generations.

With the rise of decolonial studies, republican assimilationism is increasingly perceived as authoritarian and centralizing.

Réunion, a small island in the Indian Ocean, with a history marked by colonial domination and a tropical climate, cannot be satisfied with measures stemming from the technocratic thinking of Parisian politicians and civil servants to address the major issues affecting the island. The fight for Réunion’s sovereignty inevitably comes with a struggle against certain inequalities stemming from colonization: income inequality, inequalities in access to employment or property.

Movements and associations are seizing upon concepts developed by Fanon, Césaire, or Baldwin to denounce these inequalities and reclaim history.

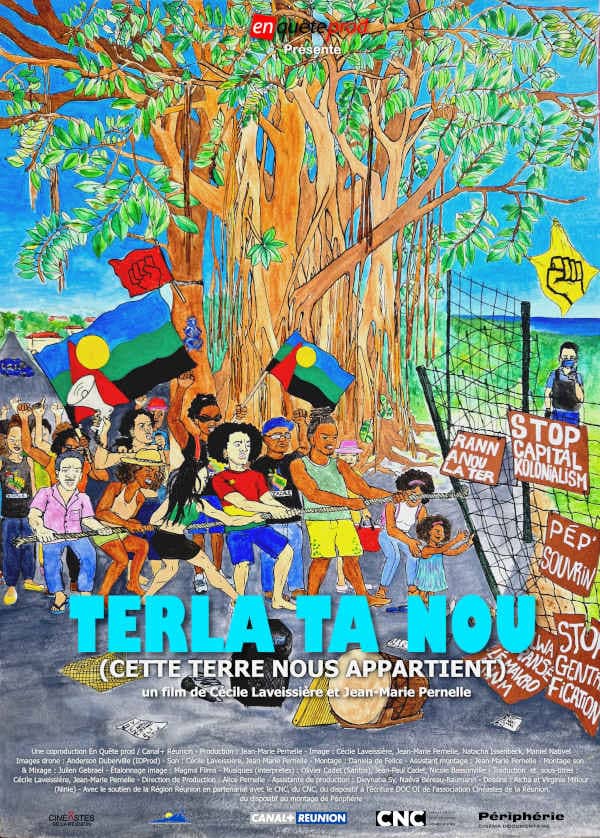

Production Note

The desire for the film arose from an encounter with a unique, symbolic place, and with the collective formed by its occupants, the QG zazalé.

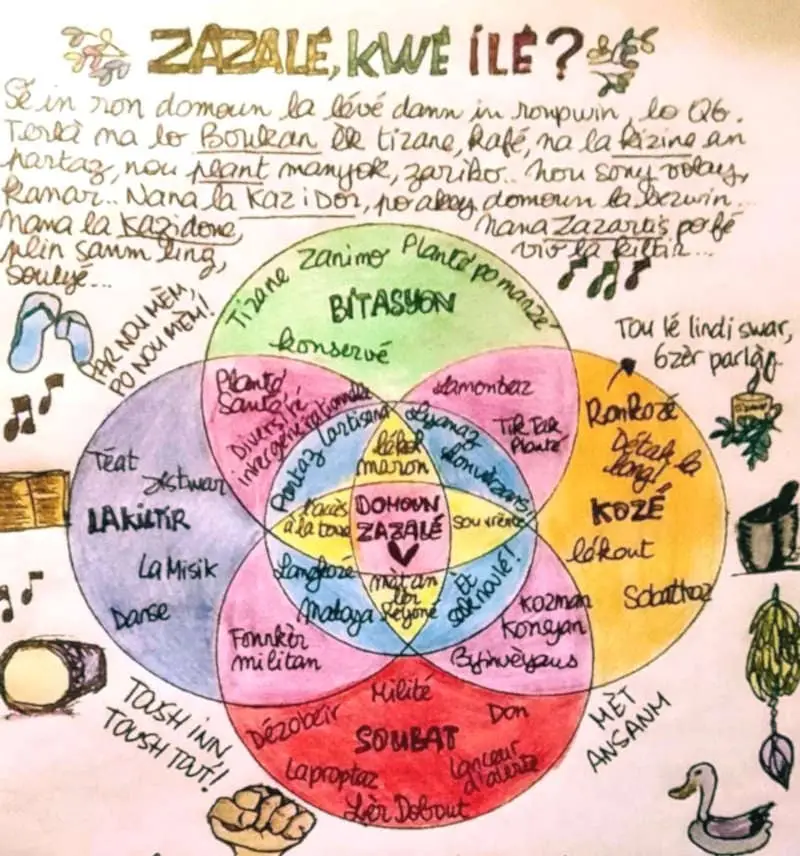

What resonated with us was the question of the relationships between the “zoreils” (metropolitan French people) and the “créoles” (locals) which is raised from the beginning of the film. “Often, the zoreils don’t know they’re zoreils until they arrive in La Réunion,” says one of the protagonists. This observation and the difficulties resulting from inequalities in living standards and access to employment between the zoreils and the créoles pose a problem. The QG zazalé and its sympathizers have taken hold of it and respond to it through the struggle for sovereignty. Political, food, ecological, and cultural sovereignty. It is articulated around major axes: sobat (struggle) – kozé (direct democracy) – bitasyon (planting to eat, food self-sufficiency) – kiltir (defense of Réunionese Creole culture and language). At the center of these axes, as a source of initiative and objective, domoun (humanity). And it is based on the reclaiming of the land, the land that belongs to the State, perceived as authoritarian and colonial.

The political dimension of the project, accompanied by numerous actions of social solidarity, strikes us with its audacity. It fully inscribes itself in post-colonial movements in Africa and the Caribbean, and in the emergence of decolonial studies in the current debate.

Our intention is to document, without pretension, this historical experience in La Réunion. What interests us is to understand how this alternative works, even on a small scale at a roundabout, what place our society leaves for such a project, and what oppositions and resistances it encounters.

We want to explore with the audience this utopia at work with its strengths and weaknesses, with its ideals and contradictions, with its tensions and moments of grace. What is happening here is fragile and perhaps ephemeral. It is this moment of experimentation that we want to capture. It is also a form of struggle that leaves plenty of room for joy and the happiness of doing things together.

Directing Approach

We shot in immersion over a total of three years. The choice of direct cinema is suitable for the multiplicity of actions carried out on the roundabout and off the roundabout: cleaning a ravine where the QG zazalé cultivated a garden and a police charge at Manapany during a demonstration against the privatization of the garden overlooking the basin.

We chose to stay mostly on the roundabout to be as close as possible to the protagonists and the construction of their project in its multiple dimensions.

The film focuses on a very short period, between 2020 and 2021, leading up to the struggle against the gentrification of Manapany. During this period, the QG zazalé seeks land to establish a village and practice food self-sufficiency, while also raising the question of land access in La Réunion. This question leads to a deeper reflection on economic and social inequalities between the zoreils and the créoles. And it points to the responsibility of a centralizing and authoritarian State.

In the editing, we chose to prioritize the decolonial narrative arc and to enrich it with secondary narrative arcs such as the search for land and the struggle against gentrification.